POWAR STEAM allows teachers and students to simulate weather conditions, experiment with real data and promote digital and environmental skills in the classroom.

By Miguel Ángel Ossorio Vega / Rubén Permuy, UOC

Science has been warning of the risks of climate change from global warming for decades. But only the highest scientific authorities have appropriate models to understand in depth the magnitude of a set of phenomena that, in addition, are currently fighting against the hoaxes and misinformation surrounding policies and measures to curb global warming and protect the regions and people that are estimated to be most affected by climate change.

With this context in mind, POWAR STEAM was born, a start-up that has designed a climate simulator focused on teaching so that students can better understand the vicissitudes of climate change. "The project is based on a climate simulator designed for farmers who want to understand the climate of the future in different cities, because, as a study by ETH Zurich points out, in 2050 Barcelona and Madrid could have the climate of Marrakech.

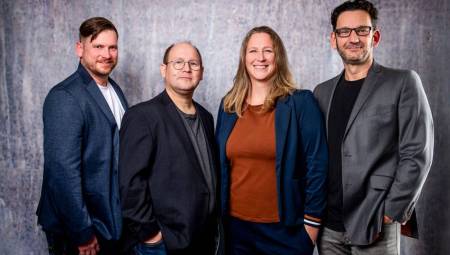

I thought: How can we help farmers test the plants of the future today in a changing climate?" explains Pablo Zuloaga, a participant in EduTECH Emprèn and founder of POWAR STEAM, a project whose focus shifted from "bringing tools to farmers, to bringing them to schools so that they can experiment and collect data that, in the future, will be used to create a new one." they can also be useful for the agricultural sector," he adds.

Learning by experimenting

The project proposes a STEAM approach – Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics – so that "students not only understand and memorise problems, but also dare to solve them. That they can propose real solutions through data and emerging technologies," he points out.

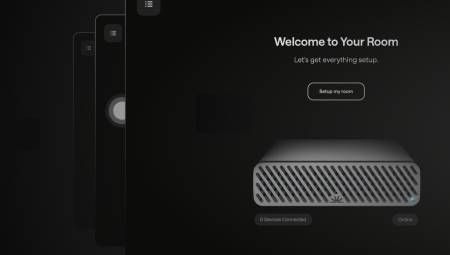

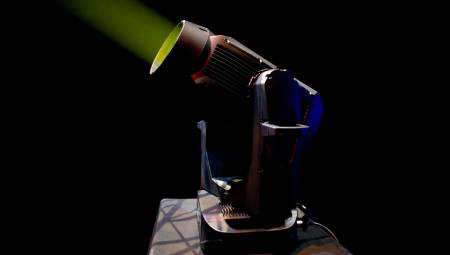

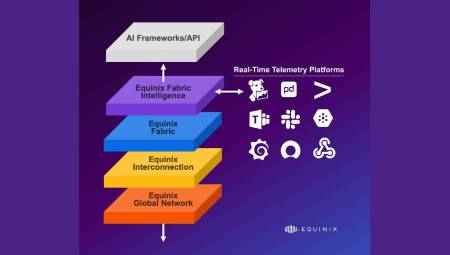

To do this, POWAR STEAM consists of a weather simulator and an environmental mini-computer called P-Bit. The first is a box for growing plants connected to the internet and equipped with sensors and actuators that generate rain, cold or heat; climatic conditions that can be configured through a digital platform that "compares the climate they have selected with the conditions of the box" to reproduce it and see how this would affect the plants grown in it, Zuloaga explains.

Both teachers and students can select on an interactive map the region whose climate they want to simulate in the box that they will have available in the classrooms. "In some tests that we have done, students have fun with the map, so understanding latitudes, tropical areas or that there are places in the world with few hours of daylight or night every day are things that they can also learn to have climate resilience," says the creator of this project, which allows schools to generate, collect and share data with other schools and institutes anywhere in the world where they are also using their platform.

Although the climate simulator gave rise to the project, today the main focus of POWAR STEAM is the development and implementation of the P-Bit, that mini-environmental computer designed for the classroom. This self-contained, easy-to-use device equipped with integrated sensors, allows students to measure variables such as temperature, soil moisture, air quality or light in real time.

It is already being used in pilot schools as a transversal tool to work on sustainability from different subjects, and responds to a specific demand of teachers: to have accessible, practical resources aligned with the educational curriculum.

Versatility and adaptability

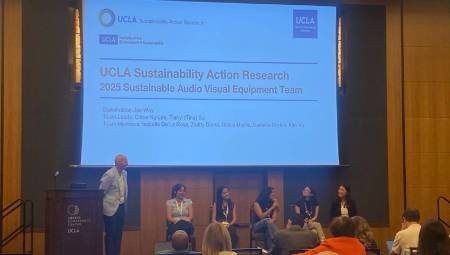

So far, the P-Bit has been tested in eight schools: five in Catalonia and three in Croatia, with more than 350 students and 50 teachers participating. The goal is to reach 1,500 schools and 90,000 students in the next five years. "We are developing a collaborative platform where teachers, students and families can share experiments, generate open data and build an educational community around sustainability," says Pablo Zuloaga.

To achieve this capillarity, POWAR STEAM includes a set of sensors and devices prepared to generate the events and situations that must be simulated, but it is also compatible with third-party sensors so that each educational center, subject and teacher can squeeze the most out of their capabilities. In fact, Zuloaga explains that they are currently training a specific artificial intelligence model so that teachers and students can pose the specific situation they want to simulate and the algorithm advises them on the specific configuration of the climate computer that they must make to obtain it.

POWAR STEAM, which emerged as one of the finalists of SpinUOC 2025, the UOC's programme to promote entrepreneurship projects, is, according to its creator, an innovative resource for teachers of any subject who want to involve their students in processes that have to do with the future of society.

"The children enjoy it a lot, they feel like scientists. It is not a toy, but it looks like it," Zuloaga highlights about a project that "arouses curiosity" in students and allows them to become "actors of change in the future." "It is useless for us to tell children that climate change is there if we do not let them propose solutions and see that they can do something to change the world," he concludes.

This entrepreneurial project is aligned with the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): 2. Zero hunger, 3. Health and well-being, 4. Quality education, 6. Clean water and sanitation, 7. Affordable and clean energy, 11. Sustainable Cities and Communities, 12. Responsible production and consumption, 13. Climate Action, 14. Underwater Life and 15. Life of terrestrial ecosystems.